Good morning. This week will be rather mad, between a new consumer price index report, a Federal Reserve meeting and a flurry of other key data drops. The market is not braced for hawkish shocks. Rather, it dares to dream, once again, of a soft landing.

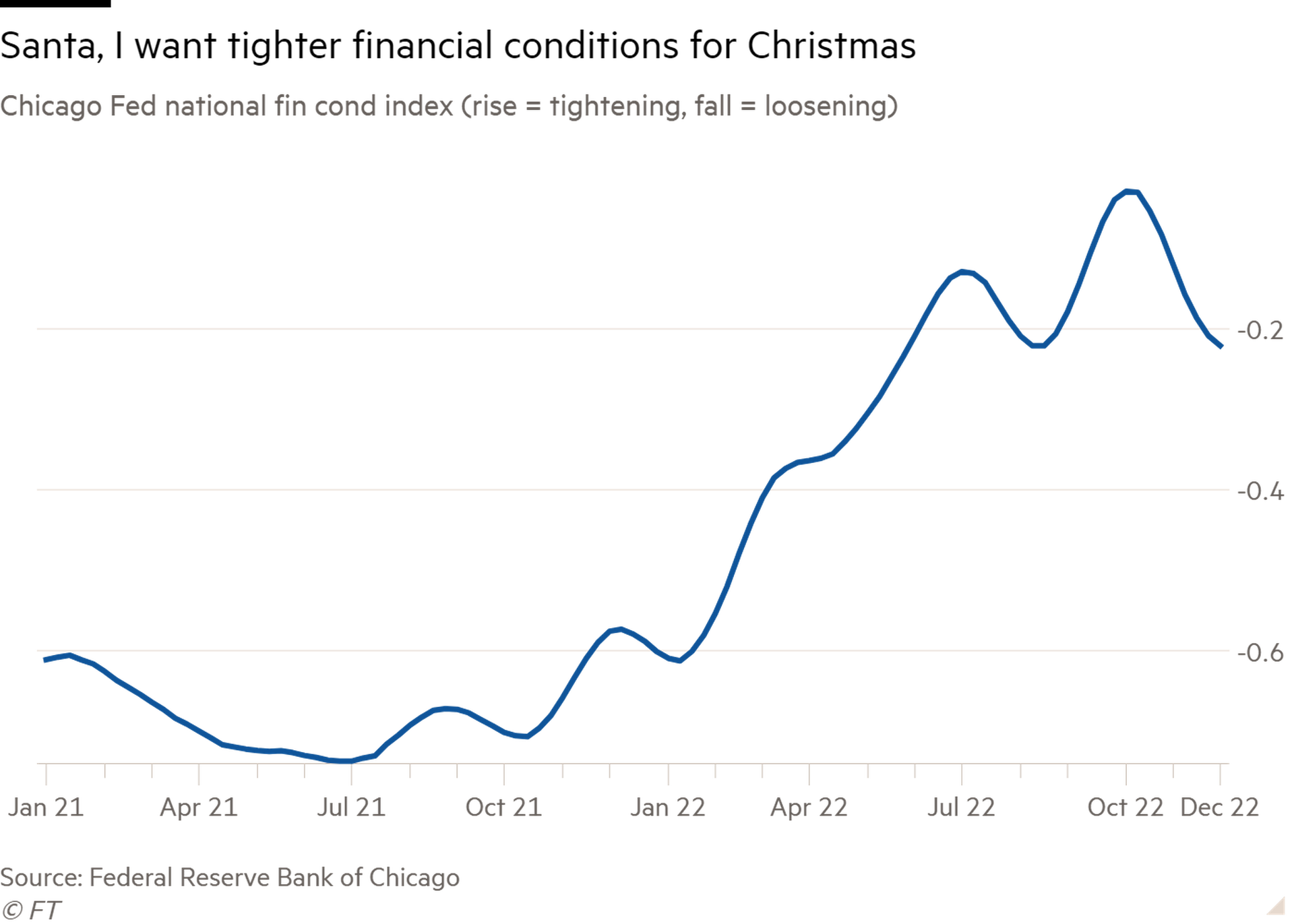

Since October, as stocks have rallied and bond yields have fallen, financial conditions have grown looser. This weekly index from the Chicago Fed stirs together 105 financial indicators, from yield spreads and stock prices to lending standards and leverage:

The Fed can』t look past this. Its whole job right now is to keep financial conditions tight. Goldman Sachs estimates that, starting next year, easier financial conditions since October will reduce the growth drag from monetary policy by a third or more.

Will this provoke Jay Powell to pound the table a bit at this Wednesday』s meeting? Maybe, but he is in a tricky spot. He has said that the lagged effects of monetary policy call for raising interest rates more gradually, even if the ultimate endpoint stays the same. Unless he drops that stance, Powell has limited room for manoeuvre. Markets expect brisk disinflation, and the Fed only has so much ability to dislodge those hopes.

A hot CPI reading on Tuesday, signalling that disinflation will be a slow grind down, would serve to tighten things up. Unhedged is putting our chips on that outcome. What say you? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

The value in value stocks, redux

Last week I wrote about how value stocks have been outperforming growth stocks this year, and made three basic points:

This value run is a reversal of a period of heavy underperformance that lasted from 2008 to 2020. Value and growth outperformance regimes tend to be long, and it looks like we might have passed an inflection point

Despite the recent outperformance, value stocks still look very cheap on the usual metrics (price

Value stocks seem to do pretty well in times of uncertainty — such these times, where inflation is providing uncertainty galore

That letter provoked an illuminating response from Unhedged』s friend Edward Finley, of the University of Virginia, discussing the theory of why value stocks tend to outperform the market over the long run. There are two schools of thought. Risk theories hold that long-term outperformance by value is compensation for value stocks』 riskiness; this is usually cashed out in terms of value stocks being issued, in many cases, by low-quality companies. Behavioural theories propose that a persistent form of irrationality is behind value』s outperformance. Finley writes:

Among the risk-based theories for the value premium is exactly the thing you . . . observe: value exhibits long periods of underperformance which is a risk for which investors demand a premium. That premium is earned over very long time horizons, and it compensates those investors for the uncertainty of owning value stocks for the long periods of underperformance.

[But] this risk-based view, in my opinion, begs the question. Why would there be long periods of value underperformance in the first place? Here behavioural theories stake a claim to understanding: investors are usually overly optimistic about the growth prospects of fast-growing companies and overly pessimistic about slower-growing companies. That causes growth stocks to earn higher returns (and value stocks to earn lower returns) than the market. But when those preferences shift (as often happens during times of distress, for example) investors race to exit growth stocks and value has a bout of strong outperformance.

What I really like about this interpretation is that it ties neatly to something else we have been writing about recently: the fact that revenue growth is not persistent and is therefore not really predictable. Humans are simply wired to extrapolate current growth rates indefinitely into the future (a type of recency bias, perhaps). The universe doesn』t work like that, however.

During good times, when prosperity and expansion are everywhere, our foolish projection of today』s growth rates years into the future seems to be confirmed by experience. But in a crisis or period of instability, the scales fall from our eyes and we are converted, like Paul, to a less speculative investment gospel. Unlike Paul, though, our faith is weak. After a few years, we fall back into sin: the belief that we can see the future. And growth stocks start outperforming again.

Finley referred me to an excellent paper about balancing the risk and behaviour theories of the value premium, written in 2014 by Clifford Asness and John Liew. It, too, argues that behaviour bias and risk may both play a role in delivering the value premium, but it contains this warning:

If value works because of a mix of rational and irrational forces, there is absolutely no reason to believe this mix is constant through time (in fact, that would be very odd). In our view, it』s likely that at most times risk plays a significant role in value』s effectiveness as a strategy . . . However, there are times when value』s expected return advantage seems like it is driven more by irrational behavioural reasons.

Things that are driven by irrationality behave, well, irrationally. Our tendency to believe, falsely, that growth is predictable is persistent, but not necessarily equally strong through time and probably not easy to predict. The takeaway is that precise timing of turns in the value

This, however, brings us back to Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates, who we quoted last week. In a series of papers, he has argued that a lot of the outperformance that appears to come from factors such as value, momentum or low volatility, is 「situational」 rather than 「structural. 」Factors come in and out of favour with investors. This favour entrenches itself over time, as performance-chasing capital flows lead to still further outperformance of a given factor. The relative valuation of a favoured factor therefore rises — this is 「situational」 outperformance. This is opposed to 「structural」 outperformance, which is something persistent rather than a reflection of investor fads. But relative valuation, which drives situational outperformance, eventually reverts to the mean.

Historically, investors have been able to take advantage of this mean reversion, when they invest in those factors that are out of favour and cheap — as value is now. But this strategy comes with a warning, too:

As with asset allocation and stock selection, relative valuations can predict the long-term future returns of strategies and factors — not precisely, nor with any meaningful short-term timing efficacy, but well enough to add material value.

Unhedged believes that valuations help determine long-term returns, so we are sympathetic to this view. But the key line is 「not precisely, nor with any meaningful short-term timing efficacy. 」Value investors have to think in terms of decades, not years.

One good read

It is hard to write something considered about Twitter. Ezra Klein has a good stab at it in the New York Times.