尊敬的用戶您好,這是來自FT中文網的溫馨提示:如您對更多FT中文網的內容感興趣,請在蘋果應用商店或谷歌應用市場搜尋「FT中文網」,下載FT中文網的官方應用。

“To the 12,750 people who ordered a single takeaway on Valentine’s Day. You OK, hun?”

「致12750名在情人節點了一人份外賣的人。你還好嗎,嗯?」

Stuck up on London underground trains by Revolut in 2019, the damning question was the fintech’s tongue-in-cheek attempt to show off its close relationship with customers.

2019年,Revolut在倫敦地鐵列車上打出了這一令人震驚的問題,這家金融科技公司試圖用開玩笑的方式展示自己與客戶的親密關係。

The ad sparked a backlash, with many taking to social media to call out not only its patronising, “single-shaming” tone, but the fact that Revolut’s private bank transaction data could be so casually publicised.

這則廣告引發了強烈反彈,許多人在社群媒體上大肆撻伐,不僅指責其頤指氣使、「羞辱單身」的語氣,還指責Revolut的私人銀行交易數據可以如此隨意地公開。

The PR disaster serves as a cautionary tale of the sensitivities around customer data in financial services, where trust and privacy are paramount to the client relationship.

這場公關災難警示了金融服務中客戶數據的敏感性,在金融服務中,信任和私隱對客戶關係至關重要。

Banks and payment companies have amassed a trove of data about clients’ financial behaviour, the rewards of which are too tempting to overlook.

銀行和支付公司積累了大量有關客戶金融行爲的數據,這些數據的回報太誘人了,讓人難以忽視。

For banks and payments companies, the question is no longer whether they can leverage their data, but how and when they will seize this opportunity

對於銀行和支付公司來說,問題不再是他們是否可以利用自己的數據,而是他們將如何以及何時抓住這個機會

While more conservative banks devote resources to “indirectly monetise” their customers’ information by offering them better-suited offers and products, the boldest disrupters — fintechs such as Revolut, Klarna and PayPal, as well as the US bank Chase — are experimenting with selling anonymised data to advertisers.

當較爲保守的銀行透過向客戶提供更適合的優惠和產品來將客戶資訊「間接貨幣化」時,最大膽的顛覆者——Revolut、Klarna和PayPal等金融科技公司以及美國大通銀行——正在嘗試向廣告商出售匿名數據。

Andreas Schwabe, managing director at consultants Alvarez & Marsal, describes the sector as being at at a “critical juncture” with regards to its use of customer data, either for internal or external purposes.

Alvarez & Marsal諮詢公司董事總經理安德烈亞斯•施瓦貝(Andreas Schwabe)認爲,銀行業正處於將客戶數據用於內部或外部目的的「關鍵時刻」。

“For banks and payments companies, the question is no longer whether they can leverage their data, but how and when they will seize this opportunity — and who will emerge as the frontrunner in this rapidly evolving landscape,” he says.

他說:「對於銀行和支付公司來說,問題不再是他們是否可以利用自己的數據,而是他們將如何以及何時抓住這個機會,以及誰將在這個快速發展的環境中成爲領跑者。」

So what exactly do banks and payment providers plan to do with your financial data? Is it safe? And is there anything you can do about it?

那麼,銀行和支付提供商計劃如何處理您的財務數據呢?安全嗎?對此你能做些什麼嗎?

The value of our financial data has been recognised for decades. “Information about money has become almost as important as money itself,” observed former Citibank chief executive Walter Wriston in 1984. Though his efforts to position the lender as a competitor to data companies such as Bloomberg largely failed, the adage is truer now than ever.

幾十年來,我們的金融數據的價值已得到認可。花旗銀行前首席執行長沃爾特•克里斯頓(Walter Wriston)在1984年指出:「有關金錢的資訊幾乎與金錢本身一樣重要。」儘管他將花旗銀行定位爲彭博社等數據公司的競爭對手的努力在很大程度上失敗了,但這句格言現在比以往任何時候都更加真實。

As the use of cash falls, more of our lives are recorded in the form of electronic payments. From friend and business networks to spending on everything from luxury handbags to charitable donations to gambling and pornography sites, much can be revealed about a person from their bank account and transaction history.

隨著現金使用的減少,我們生活中更多的事情都以電子支付的形式記錄下來。從朋友和商業網路,到奢侈品手袋、慈善捐款、賭博和色情網站等各種消費,從一個人的銀行賬戶和交易記錄中可以看出他的很多資訊。

The use of personal data is regulated differently across Europe and the US. UK legislation splits data into two categories. Sensitive, or “special category”, data includes information about racial or ethnic origin, genetics, religion, trade union membership, biometrics, health and sexual orientation. The rest is classified as non-sensitive data, which is easier for companies to handle.

歐洲和美國對個人數據的使用有著不同的規定。英國立法將數據分爲兩類。敏感數據或「特殊類別」數據包括有關種族或民族血統、遺傳學、宗教、工會會員身份、生物識別、健康和性取向的資訊。其他數據被歸類爲非敏感數據,這對公司來說更容易處理。

Transaction data is not inherently sensitive, but protected characteristics can be gleaned through analysis and enrichment — the process of improving the value of existing data by adding new or missing information.

交易數據本身並不敏感,但可以透過分析和豐富——即透過新增新資訊或缺失資訊來提高現有數據的價值——來收集受保護的特徵。

Karla Prudencio Ruiz, an advocacy officer at the research non-profit group Privacy International, gives the example of a banking customer who pays school fees at a faith school, suggesting their religion; or someone spending regularly at the oncology unit at a hospital, providing information about their health. “You can deduce things,” she says.

非營利研究組織私隱國際(Privacy International,)的宣傳官員卡拉•普魯登西奧•魯伊斯(Karla Prudencio Ruiz)舉例表示,銀行客戶在一所宗教學校支付學費,這表明了他們的宗教信仰;或者某人經常在醫院的腫瘤科消費,這提供了他們的健康資訊。她說:「你可以推斷出一些事情。」

Some fintech executives have stated that a more integrated use of customer data could shift their business model. Undeterred by its Valentine’s Day mishap, Revolut is in talks to sell advertising space on its app to brands. Antoine Le Nel, its head of growth, told the FT in April that the fintech could become a true media and advertising business in the future.

一些金融科技公司的高階主管表示,更全面地利用客戶數據可能會改變他們的商業模式。Revolut並沒有因爲情人節的失誤而氣餒,它正在洽談向品牌商出售其程式上的廣告空間。Revolut的發展主管安託萬•勒內爾(Antoine Le Nel)今年4月告訴英國《金融時報》,這家金融科技公司未來可能成爲一家真正的媒體和廣告公司。

In order to sell this to advertisers, the company, which received a UK banking licence over the summer, is looking to increase the time its customers spend browsing its financial app. Like social media companies, it keeps a close eye on its customer “engagement” metric.

爲了向廣告商出售廣告空間,這家在今年夏天獲得英國銀行牌照的公司正在尋求增加客戶瀏覽其金融程式的時間。與社群媒體公司一樣,該公司也在密切關注客戶的「參與度」指標。

Chad West, a former employee of Revolut who led its Valentine’s Day campaign, describes the ad as an “error”.

查德•韋斯特(Chad West)是Revolut的前僱員,曾領導過情人節活動,他認爲這則廣告是一個「錯誤」。

“Regardless on whether the data was aggregated or fake, it gave the impression that finance firms snoop on your every move and transaction, which is not the case.”

「不管這些數據是彙總的還是僞造的,它都給人一種金融公司窺探你一舉一動和交易的印象,而事實並非如此。」

But, he adds, the fintech’s current plan to advertise from within its banking app carries the risk of annoying customers and tarnishing its reputation for a great user experience.

但他補充說,這家金融科技公司目前在其銀行程式內做廣告的計劃有可能會惹惱客戶,並損害其良好用戶體驗的聲譽。

“It’s crucial that they perform solid due diligence on what the short-term impact could be, such as an exodus of privacy conscious customers, versus the long-term impact, such as a loss of trust in the event of a data leak or poor privacy controls.”

「至關重要的是,他們要對可能產生的短期影響(如私隱意識較強的客戶外流)與長期影響(如數據洩露或私隱控制不力導致的信任缺失)進行紮實的盡職調查。」

Zilch, another UK fintech, has built its business model on this premise. The company, which is backed by eBay and Goldman Sachs and has about 4mn customers, makes money from targeted advertising based on its transaction data which it uses to subsidise the cost of credit for consumers with zero-interest loans.

英國另一家金融科技公司Zilch就是在這一前提下建立了自己的商業模式。該公司得到了eBay和高盛的支援,擁有約400萬客戶。這家公司透過基於交易數據的定向廣告賺錢,並利用這些收入來補貼消費者的零息貸款成本。

“We’re actually an ad platform that’s built a credit proposition on top of it,” chief executive Philip Belamant told the FT in June.

首席執行長菲利普•貝拉曼特(Philip Belamant)今年6月對英國《金融時報》說:「我們實際上是一個廣告平臺,並在此基礎上建立了信貸主張。」

For all the enthusiasm, the nascent offerings are yet to prove a game-changer for banks. For Tom Merry, head of banking strategy at Accenture, a consulting firm, their benefits can be overplayed while the challenges are not necessarily worth the potential rewards.

儘管人們對此充滿熱情,但這些新生產品尚未證明能改變銀行的遊戲規則。對於諮詢公司埃森哲銀行戰略主管湯姆•梅里來說,他們的好處可能被誇大了,而面臨的挑戰不一定值得潛在的回報。

“Banks are sat on tonnes of what I would call ‘nearly useful data’,” he says, referring to “large volumes of aggregated anonymised socio-economic cohort and transaction data” that can become more valuable through enrichment.

他說:「銀行掌握著成噸的『幾乎有用的數據』,」他指的是「大量匿名社會經濟羣組和交易數據」,這些數據可以透過豐富變得更有價值。

“Sometimes people over-emphasise the value of that nearly useful data,” he continues. Banks have it, but also retailers and third party databases as well as loyalty scheme providers. “People can get it from elsewhere, probably as deeply and without having to go into the complex web of integrating with banks.”

他繼續說道:「有時人們過分強調這些幾乎有用的數據的價值。」。銀行擁有這些數據,但零售商和第三方資料庫以及忠誠度計劃提供商也擁有這些數據。「人們可以從其他地方獲得,可能同樣深入,而不必進入與銀行整合的複雜網路。」

Merry says that making substantial money from monetising data would require “scale” and “a sufficiently differentiated set of insights that people would pay a higher margin for it”. Otherwise, he says, “it’s probably not going to change the profile of a bank’s business model”.

梅里表示,要從數據貨幣化中賺取可觀的利潤,需要「規模」和「足夠與衆不同的洞察力,人們會爲此支付更高的利潤率」。他說,否則,「這可能不會改變銀行的業務模式」。

Lloyds Banking Group sees the monetisation of its 26mn customers’ financial data as an area of growth. The retail bank launched a “customer insights” team in 2022 that has grown to 40 employees.

勞埃德銀行集團將其2600萬客戶的金融數據貨幣化視爲一個成長領域。這家零售銀行於2022年成立了一個「客戶洞察」團隊,目前已有40名員工。

Lucy Stoddart, managing director of Lloyds’ global transaction solutions, said one example of this was analysing aggregated and anonymised customer data around shopping habits to provide insights to commercial real estate landlords and help them make better-informed strategic decisions.

勞埃德銀行全球交易解決方案董事總經理露西•斯托達特(Lucy Stoddart)表示,其中一個例子是分析圍繞購物習慣的彙總和匿名客戶數據,爲商業房地產房東提供見解,幫助他們做出更明智的戰略決策。

The potential for data breaches risks damaging the trust between customers and the institutions holding and managing their money.

數據洩露的潛在風險會損害客戶與持有和管理其資金的機構之間的信任。

A report by consultancy Thinks Insights and Strategy found that people perceive sharing their credit and debit transactions as more risky than other types of data, including health information, because the benefits of doing so are less clear.

諮詢公司Thinks Insights and Strategy的一份報告發現,人們認爲共享信用和借記交易比其他類型的數據(包括健康資訊)風險更大,因爲這樣做的好處不太明顯。

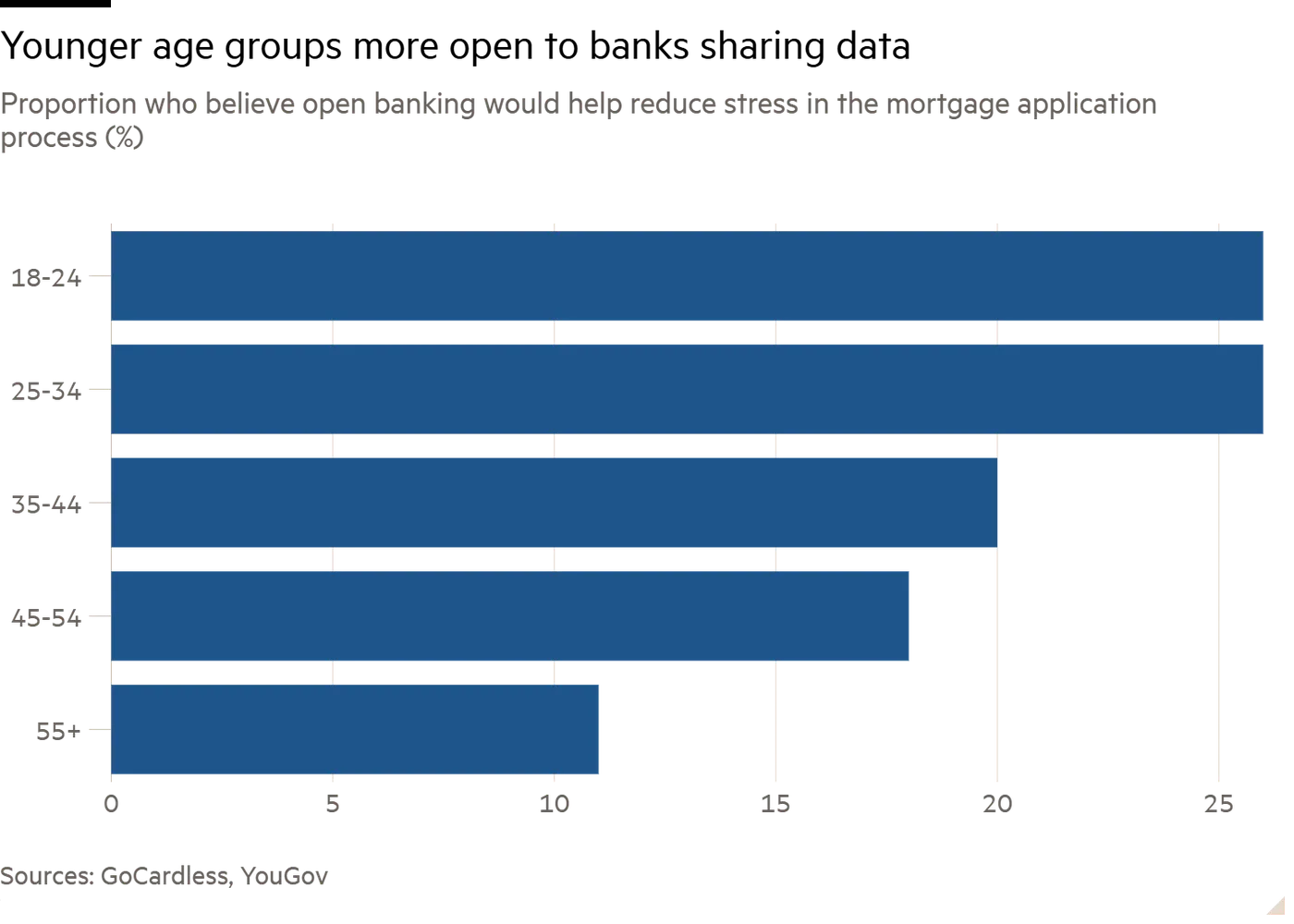

Young people aged between 18 and 24 years tend to worry about data sharing less than their older peers. However, that may be because they have been sharing it their whole lives, according to the Office for National Statistics.

與年齡較大的同齡人相比,18至24歲的年輕人對數據共享的擔心往往較少。不過,根據國家統計局的數據,這可能是因爲他們一生都在分享數據。

Donna Sharp, a managing director at MediaLink, which helps companies including in financial services to run media campaigns, says analysing customer data is an essential part of the service that banks and payment companies provide.

MediaLink的董事總經理唐娜•夏普(Donna Sharp)表示,分析客戶數據是銀行和支付公司提供的服務的重要組成部分。MediaLink幫助包括金融服務在內的公司開展媒體活動。

“The reality is that all these financial institutions have your data; you want them to [have it]. It protects you,” says Sharp. She gives the example of banks figuring out whether a card was stolen via behavioural pattern analysis and geolocation data.

夏普說:「現實情況是,所有這些金融機構都有你的數據;你希望他們(擁有這些數據)。這可以保護你。」她舉了一個例子,銀行透過行爲模式分析和地理位置數據來確定銀行卡是否被盜。

[As] more data flows, what you end up with over time . . . is much more personal pricing: you get the right price for you based on your credit risk

(隨著)更多數據的流動,隨著時間的推移......你最終得到的是更加個性化的定價:根據你的信用風險,你會得到適合你的價格

The challenge, she says, is fostering greater “transparency and understanding of how that might be used and what’s the value to you.” She believes consumers are generally fine with their data being used as long as they can see the benefits trickle down to them.

她表示,目前的挑戰是提高「透明度,讓人們瞭解如何使用這些數據,以及這些數據對您的價值」。她認爲,只要消費者能看到好處逐漸惠及他們,他們一般都能接受。

“If [I’m getting] 10 per cent off a trip I want to go on, I’m not mad that you brought that information to me,” says Sharp.

夏普說:「如果我想去的旅行能獲得10%的折扣,我不會因爲你把這些資訊帶給我而生氣。」

In the UK, the open banking industry, which allows financial companies to access to non-anonymised bank data with the permission of customers, was built on the promise that sharing data in this way would foster greater competition and ultimately benefit customers.

在英國,開放銀行業允許金融公司在獲得客戶許可的情況下訪問非匿名銀行數據,其基礎是以這種方式共享數據將促進更大的競爭並最終使客戶受益。

Justin Basini, chief executive of credit report company ClearScore, says data-sharing technology can allow lenders to access information previously only accessible by banks, known as “current account turnover”, in addition to credit reports and scoring. Seeing a fuller picture of prospective borrowers’ financial health allows lenders to adjust their rates and extend credit to more people.

信用報告公司ClearScore的首席執行長賈斯汀•巴西尼表示,除了信用報告和評分外,數據共享技術還可以讓貸款人訪問以前只有銀行才能訪問的資訊,即「經常賬戶週轉率」。看到潛在借款人財務健康狀況的更全面情況,可以讓貸款人調整利率,並向更多人提供信貸。

“[As] more data flows, what you end up with over time . . . is much more personal pricing: you get the right price for you based on your credit risk, and you’re not bucketed with other people,” says Basini.

巴西尼說:「(隨著)更多數據的流動,隨著時間的推移......你最終得到的是更加個性化的定價:根據你的信用風險,你會得到適合你的價格,而且你不會和其他人被混在一起。」

“If the market is basically more able to discriminate risk because there’s more data around, everybody gets a fairer price.”

巴斯尼說:「如果市場因爲有了更多的數據而從根本上提高了辨別風險的能力,那麼每個人都能得到更公平的價格。」

ClearScore also gives “credit health” scores by using open banking to analyse transaction data to show customers how specific payments such as gambling may affect their options with lenders. Under open banking legislation, ClearScore requires explicit permission from consumers, which has to be renewed every 12 weeks through various loops including ID checks.

ClearScore還利用開放銀行分析交易數據,爲客戶提供「信用健康」評分,向客戶展示賭博等特定支付行爲會如何影響他們在貸款機構的選擇。根據開放銀行立法,ClearScore需要消費者的明確許可,並且每12周必須透過包括身份證檢查在內的各種循環重新獲得許可。

Stopping your financial data from being used by your bank or payment provider is tricky. In the UK, any company handling customer data has to comply with a variety of rules. For instance, they need opt-in consent from customers and a legitimate reason to use their data. Claire Edwards, data protection partner at law firm Addleshaw Goddard, says another important principle they need to stick to is “data minimisation” — not collecting more information than is needed.

阻止銀行或支付提供商使用您的財務數據非常棘手。在英國,任何處理客戶數據的公司都必須遵守各種規則。例如,他們需要獲得客戶的同意,並有合法理由使用他們的數據。Addleshaw Goddard律師事務所數據保護合夥人克萊爾•愛德華茲(Claire Edwards)表示,他們需要遵守的另一個重要原則是「數據最小化」——不收集超出需要的資訊。

But this only applies to data that identifies people.

但這隻適用於能識別個人身份的數據。

“Once it’s anonymised, it falls outside our regime. The banks are probably already doing whatever they want with that,” she says. “As a consumer you can’t really opt out of that.”

「一旦匿名,就不在我們的監管範圍內。銀行可能已經在做任何他們想做的事情了。」她說,「作爲消費者,你無法真正選擇退出。」

Under UK privacy law, individuals can send “data subject access requests” (DSARs) to ask companies if they are using and storing their personal data, and request copies of this information. Companies have 30 days to respond under the Data Protection Act.

根據英國私隱法,個人可以發送「數據主體訪問請求」(DSAR),詢問公司是否在使用和存儲他們的個人數據,並要求提供這些資訊的副本。根據《數據保護法》,公司有30天的時間做出回應。

One high-profile case saw politician Nigel Farage send such a request to private bank Coutts after it closed his account. The bank was then obliged to send him a dossier that revealed its reputational risk committee had accused him of “pandering to racists” and being a “disingenuous grifter”.

在一個備受矚目的案例中,政客奈傑爾•法拉奇(Nigel Farage)在私人銀行Coutts關閉其賬戶後向該銀行發出了這樣的請求。該銀行隨後不得不向他發送了一份檔案,其中顯示其聲譽風險委員會指責他「迎合種族主義者」,是一個「虛僞的騙子」。

15%Increase in complaints about data subject access requests in the year to April 2024

15%截至2024年4月的一年中,有關數據主體訪問請求的投訴有所增加

Customers dissatisfied with DSARs can also complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office, the UK’s privacy watchdog. Such claims have jumped 15 per cent in the year to the end of April, a freedom of information request sent by consultancy KPMG found. Complaints about financial companies’ responses to DSARs made up the largest share of the total, ahead of the health sector.

對DSAR不滿意的客戶還可以向英國私隱監管機構資訊專員辦公室投訴。諮詢公司畢馬威(KPMG)發出的資訊自由申請發現,截至4月底的一年中,此類投訴猛增了15%。關於金融公司對DSAR回覆的投訴在總數中所佔比例最大,超過了衛生部門。

This could be because financial companies — and particularly banks built on a patchwork of IT systems — may struggle to source data quickly and present it in a readable way. They also have to leave out information that may breach anti-financial crime regulations. Bank employees are criminally liable for “tipping off” — disclosing information that could prejudice an ongoing or potential law enforcement investigation into a customer’s activities.

這可能是因爲金融公司,尤其是建立在零散IT系統基礎上的銀行,可能難以快速獲取數據並以可讀的方式呈現。此外,它們還必須刪除可能違反反金融犯罪法規的資訊。銀行員工如果「告密」——披露可能妨礙正在進行或可能進行的客戶活動執法調查的資訊——將承擔刑事責任。

Privacy International is campaigning against the UK’s data protection and digital information bill, which would give the government powers to monitor bank accounts to detect red flags for fraud and error in the welfare system.

私隱國際正在反對英國的數據保護和數字資訊法案,該法案將賦予政府監控銀行賬戶的權力,以發現福利系統中欺詐和錯誤的危險信號。

The campaign group raised alarm around the “extraordinary” scope of these powers. It says they will set a “deeply concerning precedent for generalised, intrusive financial surveillance in the UK” by allowing financial companies to trawl through customer accounts without prior suspicion of fraud.

該運動組織對這些權力的「非凡」範圍提出了警告。該組織稱,這些權力將允許金融公司在沒有欺詐嫌疑的情況下搜查客戶賬戶,從而爲「英國普遍的、侵入性的金融監控開創了一個令人深感憂慮的先例」。

The group says it is particularly disproportionate that the powers will allow surveillance of state benefit recipients, as well as linked accounts such as those of partners, parents and landlords.

該組織稱,尤其不相稱的是,這些權力將允許對國家福利金領取者以及伴侶、父母和房東等關聯賬戶進行監控。

“This wide scope of data collection could create a detailed and intrusive view of the private lives of those affected,” Privacy International said in a letter to former work and pensions secretary Mel Stride.

私隱國際在致前工作和養老金部長梅爾•斯特德的一封信中表示:「這種廣泛的數據收集可能會對受影響者的私人生活產生詳細而侵入性的影響。」

When it comes to banks analysing their own customer data, advocacy officer Prudencio Ruiz says consent from customers must be “informed” in order to be valid and that they should understand which information might be used, how and to what end. But they also need to be presented with a real alternative.

在談到銀行分析自己的客戶數據時,宣傳官員普魯登西奧•魯伊斯(Prudencio Ruiz)表示,客戶的同意必須是「知情」的,這樣纔有效,他們應該瞭解哪些資訊可能會被使用,如何使用以及使用的目的是什麼。但同時也需要向他們提供真正的替代方案。

“You need to be able to say OK, I don’t want to. What’s my option? And if the option is you won’t get the service, then that’s not consent.”

「你需要能夠說好的,我不想。我有什麼選擇?如果選擇是你不會得到服務,那麼這不叫同意。」