There are five days to go, but even the best coverage of the US presidential election cannot give us any sense of which way things will go. If you believe the polls, the race is a dead heat. If you believe the so-called prediction models, Donald Trump is slightly more likely to win than Kamala Harris.

I believe neither. I decided to treat polls as uninformative after the 2022 midterm elections, where many people whose judgment on US politics I trust more than mine took the polls to show a “red wave”. It didn’t happen, and I have seen no totally convincing explanation as to why that would make me trust US political polls again. (My own attempt to make sense of this concluded that not just abortion, but the economy counted in Democrats’ favour — on which more below.) The 2022 failure came on top of the poll misses in 2016 and 2020.

Not that I’m less of a poll junkie than the next journalist. Polls are captivating in the way that another hit of your favourite drug is, as my colleague Oliver Roeder suggests in his absolute must-read long read on polling in last weekend’s FT. And, of course, pollsters have been thinking hard about how they may get closer to the actual result this time. But none of this makes me think it’s wise to think polls impart more information beyond the simple fact that we don’t know.

So-called prediction models are worse, because they claim to impart greater knowledge than polls, but they actually do the opposite. These models (such as 538’s and The Economist’s) will tell you there is a certain probability that, say, Trump will win (52 per cent and 50 per cent at this time of writing, respectively). But a probability distribution is not a prediction — not in the case of a one-time event. Even a more lopsided probability does not “predict” either outcome; it says both are possible and at most that the modeller is more confident that one rather than the other will happen. A nearly 50-50 “prediction” says nothing at all — or nothing more than “we don’t know anything” about who will win in language pretending to say the opposite. (Don’t even get me started on betting markets . . . )

For something to count as a prediction, it has to be falsifiable, and probability distributions can’t be falsified by a single event. So in the case of the 2024 presidential election, look for those willing to give reasons why they make the falsifiable but definitive prediction that Trump wins, or Harris wins (or, conceivably but implausibly, neither).

At this point, it’s entirely fair to ask what I predict. From everything I have said so far, I will happily admit that I don’t know anything about who will win. But over the course of many columns, I have made some intellectual commitments, which have implications for what I should think will happen if predict I must do. So it’s time to stick my neck out.

I predict that Harris will win, and by a solid margin. Why? Largely because I think “it’s still the economy, stupid” that determines the election — and because I think the strength of the US economy is more appreciated by US voters than the electoral polling picks up. (In addition, I think the abortion issue that helped Democrats outdo expectations two years ago is, if anything, stronger today.)

The puzzle around the mismatch between strong economic outcomes (real wage growth, a strong job market, an industrial boom) and lack of support for the incumbent in electoral polling can be solved in two ways: questioning the economic data or the electoral poll results. Most observers have tried to find fault with the notion that the economy is good. For example, it’s easy to point out that while inflation has abated, prices are still a lot higher than before it took off; or that high interest rates weigh on many families’ prospects for buying a house. But there is an element of reverse engineering to this, seeking out the negatives that would explain the seeming lack of impact from a strong economy.

So I find it more plausible to question the electoral polls. That is only partly because of polling’s recent failures. It’s also because a lot of voters actually do seem happy with the economy. Properly adjusted for methodological changes, the Michigan consumer sentiment index has been on a clear upward trend since inflation peaked in the summer of 2022, and has reached levels similar to those four years ago. The Conference Board’s measure of consumer confidence, too, has picked up fairly strongly.

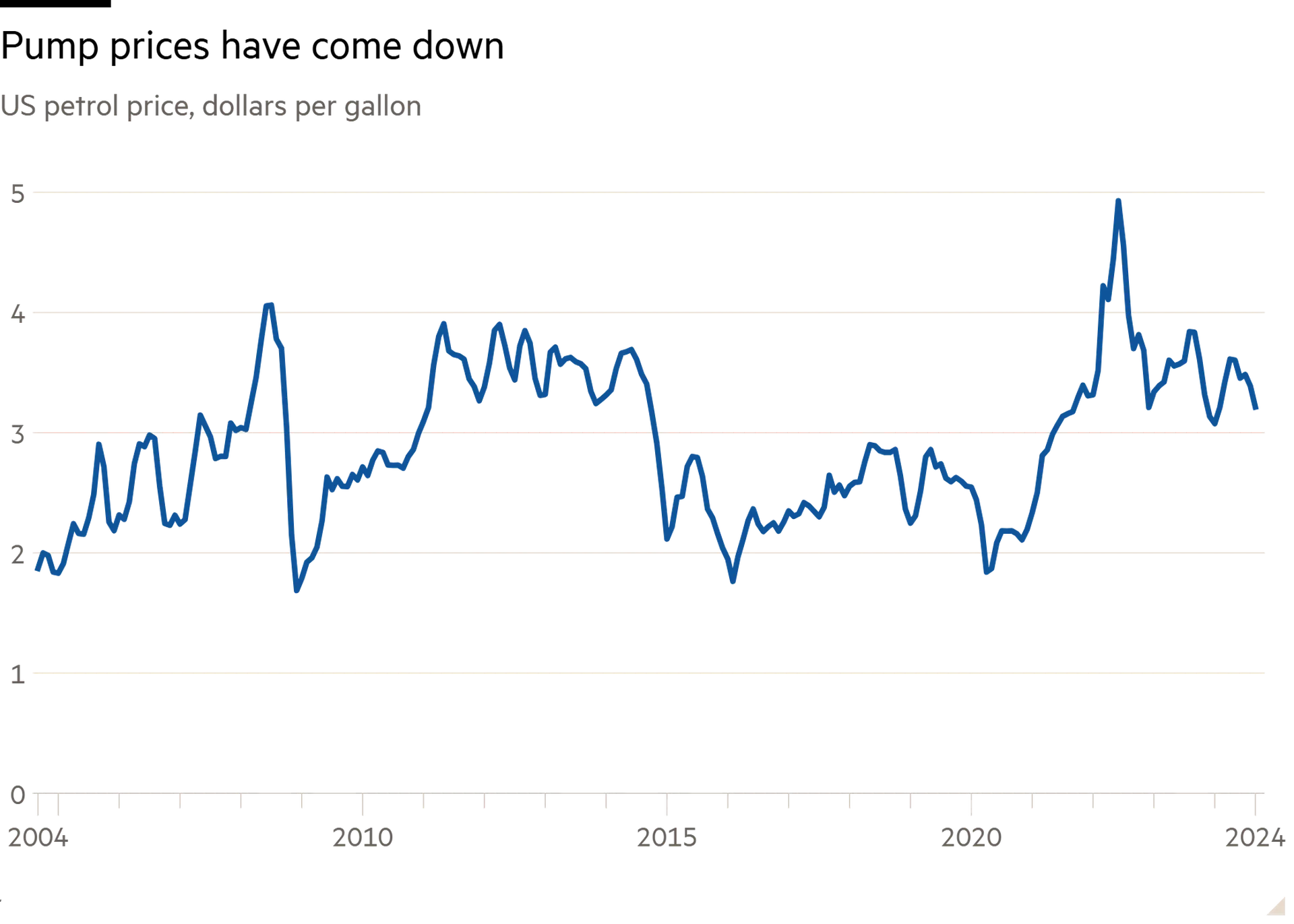

Alert readers might at this point rightly ask why I trust these surveys if I don’t trust the electoral polling. And I wouldn’t have a convincing answer — beyond pointing out that, unlike past electoral polls, sentiment surveys have largely tracked the economic reality, and returned the highest scores when labour markets have been strong, inflation low and real wages growing. I would also point to my colleague Robert Armstrong’s wonderful write-up of his visit to the mall where he observed that whatever they may say, Americans consume as if times are good (their consumption powered another strong quarter of growth in data released on Wednesday). And, above all, the facts speak for themselves, including those that have always been the most salient in US voter behaviour. Here is the petrol price — in nominal terms:

And here it is expressed in terms of working hours it would take at an average wage to buy a gallon of petrol:

There can, in other words, be little doubt that a lot of Americans are better off than four years ago. I hold on to the belief that this will in the end play out in the vote.

Sketching this argument out to a colleague, I was asked if this isn’t wishful thinking. Which of course it is. But it is wishful thinking again linked to some specific intellectual commitments set out in the columns I have devoted to “Bidenomics”, the novel economic policy approach of President Joe Biden’s team, and similar economic arguments. As Nicholas Lemann writes in a terrific piece in the New Yorker: “The irony of Bidenomics is the vast gulf between its scale — measured in money and in the number of projects that it has set in motion — and its political impact, which is essentially zero, even though a major part of its rationale is political.”

That rationale is one I have written supportively about since before Biden’s presidency. Indeed I wrote a whole book about how a new “economics of belonging” is what it would take to draw voters away from illiberal and anti-democratic populism. So I welcomed the big changes Biden presided over, and agree with how Lemann describes them today:

Objectively, and improbably, he has passed more new domestic programs than any Democratic president since Lyndon Johnson — maybe even since Franklin Roosevelt . . . Biden passed domestic legislation that will generate government spending of at least five trillion dollars, spread across a wide range of purposes, in every corner of the country. He has also redirected many of the federal government’s regulatory agencies in ways that will profoundly affect American life . . . All of this doesn’t represent merely a hodgepodge of actions. There is as close to a unifying theory as one can find in a sweeping set of government policies. Almost all the discussion of “Bidenomics” — by focusing on short-term fluctuations of national metrics such as growth, the inflation rate, and unemployment, with the aim of determining the health of the economy — misses the point. Real Bidenomics upends a set of economic assumptions that have prevailed in both parties for most of the past half century. Biden is the first president in decades to treat government as the designer and ongoing referee of markets, rather than as the corrector of markets’ dislocations and excesses after the fact.

Wishful thinking, then, insofar as I have long argued that this sort of economics should bear political fruit. And wishful thinking in one other way: although it has been a while since I lived in the US, my more than a decade there still makes me believe that there are enough voters in enough states who find the spectacle of a new Trump presidency off-putting to secure a Harris victory. Tuesday will put my confidence to the test on both counts.

Other readables

Click here for everything you need to know about Labour’s first Budget.

Happy Halloween! Here are five scary financial charts, courtesy of FT Alphaville.

Eurozone growth surprised on the upside, driven by a strong Spanish economy.

The crisis in Europe’s car manufacturing sector is mostly made in China.